I came across this ad for Android devices today.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TRmgMe2STL0

Watch it and pay close attention to these things:

- The ratio of content featuring customers vs. content featuring the product

- The fresh, down-to-earth, colloquial, customer-centric language

- The emotional impact of customers engaging with the product

- The emphasis on YOU (meaning the customer)

- The diversity of the customers shown enjoying the product

- The fresh, professional, contemporary production values

Now go get your last season brochure and pay attention to these things:

- The ratio of content featuring customers vs. content featuring the product

- The fresh, down-to-earth, colloquial, customer-centric language

- The emotional impact of the customers engaging with the product

- The emphasis on YOU (meaning the customer)

- The diversity of the customers shown enjoying the product

- The fresh, professional, contemporary production values

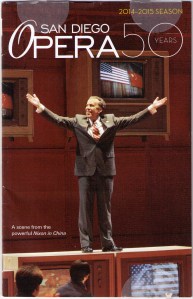

In my last post I drew attention to some shamelessly egocentric marketing materials that were produced by big financially troubled arts institutions (Minnesota Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony, San Diego Opera). This Android ad, by demonstrating so well what good marketing is about, shows exactly why those arts marketing materials are so bad:

- Their content is entirely about the product

- Their language is canned, stuck up, artsy and self-centered

- They tell customers what they should feel rather than showing them how they will feel

- Their emphasis is on US (meaning the product)

- There is no diversity of customers shown enjoying the product because there are no customers shown enjoying the product

- Their production values are stale, amateurish and old-fashioned

Make no mistake. The blame for failing to attract sustaining audiences lies squarely with executive leaders who allow their organizations to do narcissistic marketing.

When troubled arts organizations start developing marketing content that’s about new audiences – and how their products will make those audiences happy – they’ll earn the customers they deserve.